Free Courses Sale ends Soon, Get It Now

Free Courses Sale ends Soon, Get It Now

The Economic Survey rightly flagged the issue of a growing food subsidy bill, which, in the words of the government, “is becoming unmanageably large.”

Food subsidy, coupled with the drawl of food grains by States from the central pool under various schemes, has been on a perpetual growth trajectory.

During 2016-17 to 2019-20, the subsidy amount clubbed with loans taken by the Food Corporation of India (FCI) under the National Small Savings Fund (NSSF) towards food subsidy, was in the range of Rs.1.65-lakh crore to Rs.2.2-lakh crore.

In future, the annual subsidy bill of the Centre is expected to be about Rs 2.5-lakh crore. Even the Economic Survey 2020-21 has made important recommendations to improve the Public Distribution System.

Definition: Public distribution system is a government-sponsored chain of shops entrusted with the work of distributing basic food and non-food commodities to the needy sections of the society at very cheap prices.

Wheat, rice, kerosene, sugar, etc. are a few major commodities distributed by the public distribution system.

Description: Food Corporation of India, a government entity, manages the public distribution system. The system is often blamed for its inefficiency and rural-urban bias. It has not been able to fulfill the objective for which it was formed. Moreover, it has frequently been criticized for instances of corruption and black marketing.

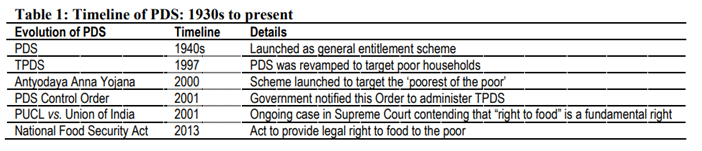

1940s: India’s Public Distribution System (PDS) is the largest distribution network of its kind in the world. PDS was introduced around World War II as a war-time rationing measure.

1960s: Before the 1960s, distribution through PDS was generally dependant on imports of food grains. It was expanded in the 1960s as a response to the food shortages of the time; subsequently, the government set up the Agriculture Prices Commission and the Food Corporation of India to improve domestic procurement and storage of food grains for PDS.

1970s: By the 1970s, PDS had evolved into a universal scheme for the distribution of subsidised food. In the 1990s, the scheme was revamped to improve access of food grains to people in hilly and inaccessible areas, and to target the poor.

1990s: Subsequently, in 1997, the government launched the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS), with a focus on the poor. TPDS aims to provide subsidized food and fuel to the poor through a network of ration shops. Food grains such as rice and wheat that are provided under TPDS are procured from farmers, allocated to states and delivered to the ration shop where the beneficiary buys his entitlement. The centre and states share the responsibilities of identifying the poor, procuring grains and delivering food grains to beneficiaries.

2000s: In September 2013, Parliament enacted the National Food Security Act, 2013. The Act relies largely on the existing TPDS to deliver food grains as legal entitlements to poor households. This marks a shift by making the right to food a justiciable right.

Up to 79.56% of the rural population and 64.43% of the urban population will be covered under TPDS, with uniform entitlement of 5 kg per person per month.

Note: The government does not identify APL households; therefore, any household above the poverty line is eligible to apply for a ration card. The centre allocates food grains to states for APL families in addition to BPL families; however, this allocation is based on the availability of food grains in the central stocks and the average quantity of food grains bought by states from the center over the last three years. Hence, the allocation to a state increases if it’s off take increases over the previous years.

The food grains provided to beneficiaries under TPDS are procured from farmers at MSP. The MSP is the price at which the FCI purchases the crop directly from farmers; typically the MSP is higher than the market price. This is intended to provide price support to farmers and incentivize production. Currently procurement is carried out in two ways:

The centre procures and stores food grains to:

The central government introduced the Open Market Sale Scheme (OMSS) in 1993, to sell food grains in the open market. This was intended to augment the supply of grains to moderate or stabilize open market prices.

Identification of beneficiaries

Studies have shown that targeting mechanisms such as TPDS are prone to large inclusion and exclusion errors. This implies that entitled beneficiaries are not getting food grains while those that are ineligible are getting undue benefits. An expert group in 2009 estimated that about 61% of the eligible population was excluded from the BPL list while 25% of non-poor households were included in the BPL list.

Ghost Cards

“Ghost cards” are cards made in the name of non-existent people. The existence of ghost cards indicates that grains are diverted from deserving households into the open market.

Production vs Procurement

Under the National Food Security Act, the centre procures millions of tonnes of food grains consistently every year to deliver rights under the law. Procurement of this quantity of food grains might be easier in years when production is high. However, in years of drought and domestic shortfall, India will have to resort to large scale imports of rice and wheat. This will exert significant upward pressure on prices. This further raises questions regarding the Government’s ability to procure grains without affecting open market prices and adversely impacting the food subsidy bill.

Allocation and offtake of food grain

The centre allocates food grains to states on the basis of the identified BPL population, the availability of food grains stocks, and the quantity of food grains lifted by states for distribution under TPDS. The allocation to a state changes every year on the basis of the state’s average consumption over the last three years.

However, according to the CACP, based on 2009-10 data from the National Sample Survey, consumption under TPDS was only 60% of the total offtake. This implies that nearly 40% of offtake is being leaked into the open market.

Rising food subsidy

The food subsidy has increased over the years, having more than quadrupled from Rs 21,200 crore in 2002-03 to Rs 2.2-lakh crore in 2019-2020.

The factors that contribute to the rising food subsidy are:

Imbalances in the availability of storage capacity across states

There is an imbalance in the availability of storage capacity across regions. On the one hand, there is a shortage of space in consuming states, such as Rajasthan and Maharashtra, and on the other hand, 64 percent of the total storage capacity is concentrated in states undertaking large procurement such as Punjab, Haryana, Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Chhattisgarh.

Maximum buffer norms not specified:

The minimum buffer norms prescribed by the government do not clearly delineate individual elements of food security (e.g., emergency, price stabilization, food security reserve, and TPDS) within the minimum buffer stock. The existing norms also do not specify the maximum stock that should be maintained in the central pool for each of the above components.

Low utilisation of existing capacity in various states/UTs:

CAG audit observed that despite storage constraints in FCI, utilization of existing storage capacity in various states/UTs is abysmal.

|

Supreme Court order on rotting of food grains in storage In August 2010, in the ongoing case of PUCL vs. Union of India, the Supreme Court found that food grains were rotting due to inadequate storage. It directed the central government to adopt long and short term measures to store and preserve procured food grain, and prevent rotting, including:

|

Leakage of food grains

TPDS suffers from large leakages of food grains during transportation to and from ration shops into the open market. In an evaluation of TPDS, the Planning Commission found 36% leakage of PDS rice and wheat at the all-India level.

Issue prices and politics

Central Issue Price (CIP), has remained at Rs. 2 per kg for wheat and Rs. 3 per kg for rice for years, though the NFSA, even in 2013, envisaged a price revision after three years.

What makes the subject more complex is the variation in the retail issue prices of rice and wheat, from nil in States such as Karnataka and West Bengal for Priority Households (PHH) and Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) ration card holders, Rs. 1 in Odisha for both categories of beneficiaries to Rs. 3 and Rs. 2 in Bihar for the two categories.

The Centre stated that “the economic cost of food management in view of rising commitment” towards food security, does not want the NFSA norms to be disturbed.

But, a mere increase in the CIPs of rice and wheat without a corresponding rise in the issue prices by the State governments would only increase the burden of States, which are even otherwise reeling under the problem of a resource crunch.

According to a UIDAI paper by the Planning Commission, integration with Adhaar as has been done would help eliminate duplicate and fake beneficiaries and make identification for entitlements more effective.

There are some alternatives to TPDS, which address some problems during implementation. Tamil Nadu implements a Universal rather than a Targeted PDS.

Experts have noted that PDS could be replaced with cash transfers or food coupons.

|

Case study: Universal PDS in Tamil Nadu Non-classification of beneficiaries - Subsidised PDS commodities are distributed to all residents without classifying them into different categories. According to the Justice Wadhwa Committee Report, non-classification helps the state avoid errors of exclusion of eligible and vulnerable families. However, TN identifies AAY beneficiaries. Commodities provided under universal PDS - Rice is distributed at the price of Re 1/ kg to everyone, lower than the central issue price. Families are not given 35 kg as mandated by the central government; rice cardholders get anywhere between 12-20 kg rice depending on the number of individuals in their family. Groups involved in the distribution of food grains - No private trader is engaged in the PDS activity. Ration shops are mainly run by the cooperative societies and the Tamil Nadu Civil Supplies Corporation, the FCI counterpart in the state. |

Cash Transfers

The National Food Security Act, 2013 includes cash transfers and food coupons as possible alternative mechanisms to the PDS. Beneficiaries would be given either cash or coupons by the state government, which they can exchange for food grains. Such programmes provide cash directly to a target group – usually poor households.

Potential advantages of these programs include:

Downsides:

Food coupons

Food coupons are another alternative to PDS. Beneficiaries are given coupons in lieu of money, which can be used to buy food grains from any grocery store. Under this system, grains will not be given at a subsidized rate to the PDS stores. Instead, beneficiaries will use the food coupons to purchase food grains from retailers (which could be PDS stores). Retailers take these coupons to the local bank and are reimbursed with money. According to the Economic Survey 2009-10 reports, such a system will reduce administrative costs. Food coupons also decrease the scope for corruption since the store owner gets the same price from all buyers and has no incentive to turn the poor buyers away. Moreover, BPL customers have more choice; they can avoid stores that try to sell them poor-quality grain.

Issues

Some problems could exist while designing such a system. Food coupons can be counterfeited. Regular delivery of food coupons to the intended beneficiaries could also pose logistical challenges; there is a need to ensure the timely reimbursement of subsidy to the participating retailers.

PDS vs Cash Transfer

Give Up Option

It should revisit NFSA norms and coverage. An official committee in January 2015 called for decreasing the quantum of coverage under the law, from the present 67% to around 40%. For all ration cardholders drawing food grains, a “give-up” option, as done in the case of cooking gas cylinders, can be made available.

Even though States have been allowed to frame criteria for the identification of PHH cardholders, the Centre can nudge them into pruning the number of such beneficiaries.

Slab System

As for the prices, the existing arrangement of flat rates should be replaced with a slab system. Barring the needy, other beneficiaries can be made to pay a little more for a higher quantum of food grains.

The rates at which these beneficiaries have to be charged can be arrived at by the Centre and the States through consultations.

Under Public Distribution System (PDS) reforms, digitization of ration cards/beneficiaries and distribution of highly subsidised foodgrains, namely- Rice, Wheat and Coarse-grains, to targeted beneficiaries under NFSA through electronic Point of Sale (ePoS) devices, after biometric/Aadhaar authentication of beneficiaries are key objectives to improve the efficiency and transparency in the distribution process.

At present, nearly 90% of the total 23.4 Crore ration cards under NFSA across the country have been seeded with Aadhaar number of at least one member of the household.

The above-mentioned measures, if properly implemented, can have a salutary effect on retail prices in the open market.

A revamped, need-based PDS is required not just for cutting down the subsidy bill but also for reducing the scope for leakages. Political will should not be found wanting.

© 2024 iasgyan. All right reserved