Free Courses Sale ends Soon, Get It Now

Free Courses Sale ends Soon, Get It Now

Copyright infringement is not intended

Context: Delegates from 196 countries — Parties to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) — are meeting in Montreal, Canada from December 7-21 with the aim to hammer out a new global agreement on halting environmental loss.

Details:

· COP15 is shorthand for the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).

· In fact, COP15 includes meetings of parties to three international agreements: the CBD and its two subsidiary protocols, namely the Cartagena Protocol on biosafety and the Nagoya Protocol on access to genetic resources and fair and equitable benefit-sharing.

· The CBD was agreed at the Earth Summit in Brazil in 1992.

· It has three objectives: the conservation of biodiversity, the sustainable use of its components, and the fair sharing of benefits arising from the use of genetic resources.

· Some 195 countries and the European Union are now parties to the CBD. The United States is the only member state of the United Nations that has not ratified the agreement. The CBD’s Cartagena Protocol has 173 parties and its Nagoya Protocol has 137.

· COP15 was meant to take place in the Chinese city of Kunming in October 2020, but it was delayed four times due to the pandemic.

· To maintain momentum, China officially opened COP15 in Kunming in October 2021, a largely online event at which parties to the CBD adopted the non-binding Kunming Declaration.

· With Covid-19 restrictions still in place in China, the CBD Secretariat announced that the main part of the COP15 meeting would take place in Montreal, Canada, on 7–19 December 2022. China will remain the official President of the meeting.

Why is biodiversity important?

· Our fate is inextricably linked to that of the rest of nature.

· The latest WWF’s Living Planet Report warned that global wildlife populations declined by 69% on average from 1970 to 2018.

· The accelerating loss of nature has already impacted human well-being and economies. Healthy ecosystems also play indispensable roles in tackling climate change, and the loss of biodiversity weakens our resilience to that change.

What is the intended outcome of COP15?

· To reverse biodiversity loss, negotiations at COP15 will centre on finalising the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework.

· This is a strategy, with goals and targets for countries to achieve, individually and collectively, in the next decade and beyond.

· The aim is to set humanity on course for achieving the CBD’s overall vision of “living in harmony with nature” by 2050.

· In 2002, parties to the CBD committed “to achieve by 2010 a significant reduction of the current rate of biodiversity loss”. They failed.

· In 2010 they met in Japan and agreed on a new plan, which included the 20 Aichi Targets. But not one of these targets was fully met by the 2020 deadline.

· At the UN biodiversity conference in 2018, all parties agreed on developing new targets under a Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework to replace the Aichi Targets.

What’s different this time?

· The Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework’s goals will be more “outcome-oriented” than before, with clearly articulated and time-bound aims underpinned by targeted actions to address the drivers of biodiversity loss.

· Parties and shareholders will also pay more attention to implementation and fund raising.

· To support implementation, they will also scale up efforts to raise funds and resources from all sources.

· A CBD working group co-chaired by representatives of Canada and Uganda is developing the text of the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework for CBD parties to finalise and agree at COP15.

· The latest version has four long-term goals for 2050 and 22 targets to achieve by 2030.

· The four goals focus respectively on conservation, sustainable use of biodiversity, fair benefit-sharing, and adequate means of implementation – meaning money, as well as technical capacities.

· The targets cover a wide range of topics, from expanding protected areas and reducing pollution to ensuring that food production is sustainable and phasing out billions of dollars of public subsidies that harm nature.

Does the CBD need an apex target (like the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C)?

· Scientists, nongovernmental organisations and parties to the CBD are split about whether or not to have a top-level target to be achieved by 2030, such as an overall biodiversity status or global rate of extinction.

· Some believe it would help.

· Others say it would distract from the work of implementing the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework and that it is impossible to capture the complexity of ecosystems and species with a single metric.

Who leads the talks and why is this significant?

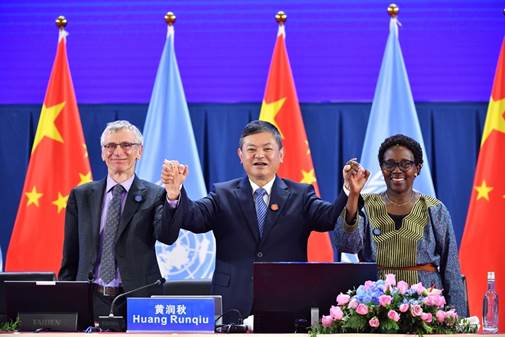

· China holds the rotating Presidency of the Conference of Parties to the CBD. Its minister of ecology and environment, Huang Runqiu, will preside over the talks in Montreal.

· It is the first time China has overseen major intergovernmental negotiations on the environment.

· This provides China with an opportunity to showcase its efforts to protect biodiversity both at home, through its vision of “ecological civilisation” and use of “ecological redlining”, and abroad, through greening its Belt and Road Initiative. But COP15 also presents a significant challenge to China.

· It will need to work hard and creatively to bring other nations together and achieve consensus on an ambitious agreement.

.jpg)

Which other countries will be key to the talks?

· Costa Rica and France co-chair the High Ambition Coalition for Nature and People, which includes more than 100 countries that support the goal of protecting 30% of land and ocean by 2030.

· Separately, leaders of 93 countries and the European Union have endorsed the Leaders’ Pledge for Nature, committing to reversing biodiversity loss by 2030.

· The members of these alliances come from all world regions and include rich and developing countries.

· But there are some notable absences, including Brazil, Indonesia and South Africa. These countries hold a large share of the world’s biodiversity, so they are influential players in the COP15 talks.

· Among other things, they will want to see firm commitments of finance from industrialised countries before they consider agreeing to other proposals.

What sticking points can we expect?

· Much of COP15 will focus on the final content of targets in the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. In these negotiations, nothing will be agreed until everything is agreed.

· While many countries want to include the target of protecting 30% of the planet, others will seek changes in other parts of the framework before agreeing to that. Argentina and Brazil, for example, are likely to resist targets that restrict agriculture.

· And while the EU strongly supports a target on pesticides, other parties are less interested. The overall outcome of COP15 will therefore depend on how parties trade off demands in some areas of the framework against concessions in others.

· One of the most significant topics the COP15 negotiators must grapple with concerns digitally stored information on genetic sequences.

· Companies could profit from such information, such as by developing new medicines without needing physical access to the species in question.

· This means they could avoid having to comply with CBD rules on sharing benefits arising from the use of genetic resources with the country of origin.

· While some parties say digital sequence information is beyond the remit of the CBD’s Nagoya Protocol on access and benefit-sharing, others say a failure to address this issue could render the protocol useless.

· As mentioned above, a major sticking point will be about “resource mobilisation”, in other words, how to fund activities to implement the new framework and, specifically, how much richer countries will provide to help poorer ones to conserve their biodiversity.

· Brazil and 22 other countries have called for rich countries to provide at least US$100 billion a year until 2030.

· That figure is in the latest draft of the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, but like much of the rest of the text, it remains up for debate in Montreal in December 2022. The big question is, will countries build on the draft and raise ambition or water down what is there?

What do the talks mean for endangered species?

· COP negotiations rarely mention individual species, but there is a proposed goal of reducing extinctions and increasing population sizes.

· Decisions made at COP15 will therefore have a bearing on the fates of everything from pangolins and jaguars to coral reefs and monkey puzzle trees – and our own species too.

Did COP27 help facilitate the success of COP15?

· The UN climate change conference COP27 in Egypt concluded less than three weeks before the kick-off of COP15 in Montreal.

· The agendas of the UN treaties on climate change and biodiversity have increasingly intersected. This reflects a growing understanding of the linkages between the two issues and the need for integrated solutions.

· The final deal struck by parties at COP27 highlighted the interconnectivity between climate and biodiversity and the urgency to address biodiversity loss.

· However, the agreement fell short of mentioning COP15. If it had, say biodiversity NGOs, that would have signalled the importance of a successful deal in Montreal to reverse biodiversity loss and fight climate change.

© 2024 iasgyan. All right reserved