Disclaimer: Copyright infringement of intended.

Context

- India may need up to 28 gigawatts of new coal-fired power plants by 2032 to meet power demand that is expected to more than double from the current 404.1 GW, a government advisory body said.

Coal

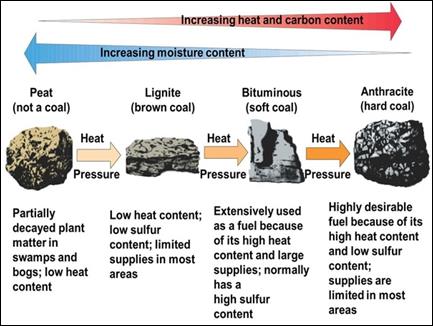

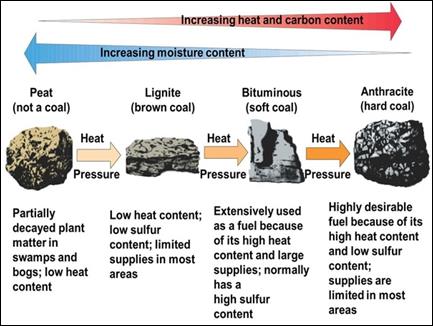

- Coal is a sedimentary deposit composed predominantly of carbon that is readily combustible.

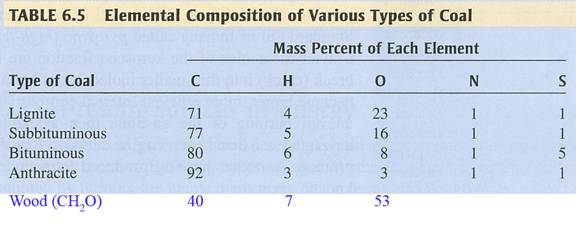

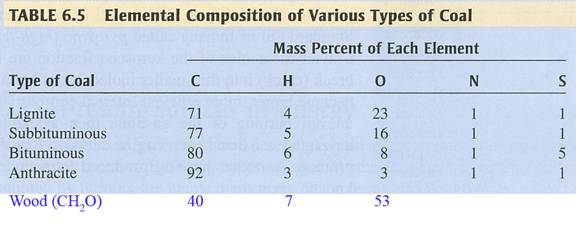

- Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

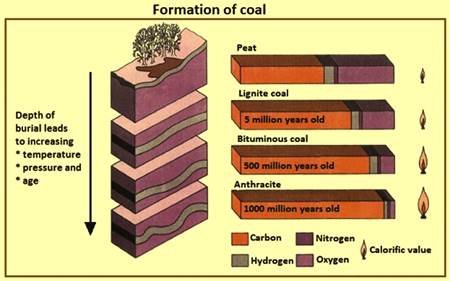

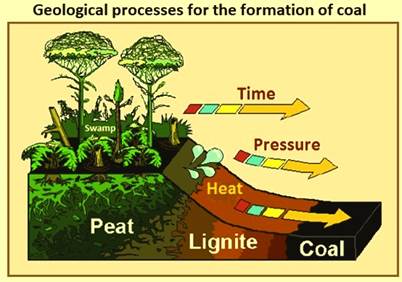

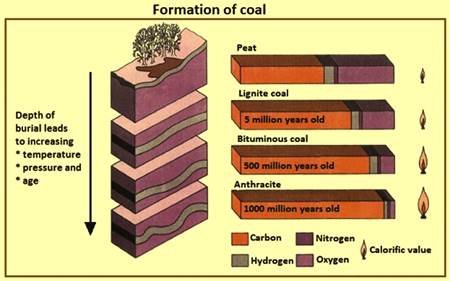

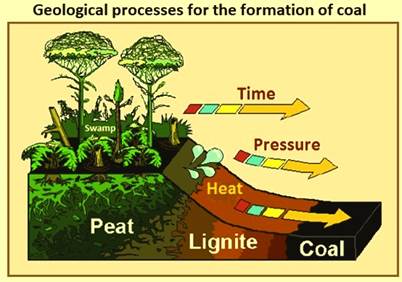

- Coal is formed when dead plant matter decays into peat and is converted into coal by the heat and pressure of deep burial over millions of years.

Types of Coal and their formation

- The process of coal formation from organic compounds includes two distinct stages namely (i) biochemical, and (ii) geochemical.In the biochemical stage the plant material had first converted into peat and then to lignite while in the geochemical stage the lignite had first converted into the bituminous coal and then to anthracite.

- Coal was formed from prehistoric plants, in marshy environments, some tens or hundreds of millions of years ago.

- The presence of water restricted the supply of oxygen and allowed thermal and bacterial decomposition of plant material to take place, instead of the completion of the carbon cycle.

- Under these conditions of anaerobic decay, in the so-called biochemical stage of coal formation, a carbon-rich material called ‘peat’ was formed.

- In the subsequent geochemical stage, the different time-temperature histories led to the formations of coal of widely differing properties. These formations of coal are lignite (65 % to 72 % carbon), sub-bituminous coal (72 % to 76 % carbon), bituminous coal (76 % to 90 % carbon), and anthracite (90 % to 95 % carbon).

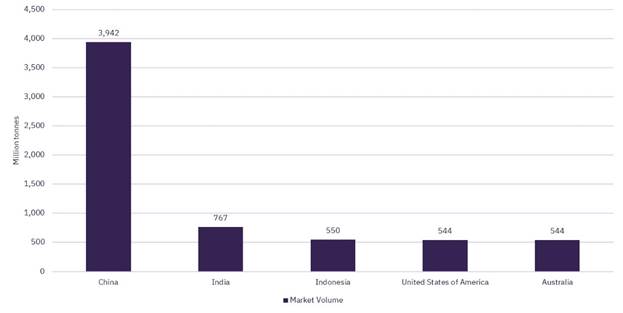

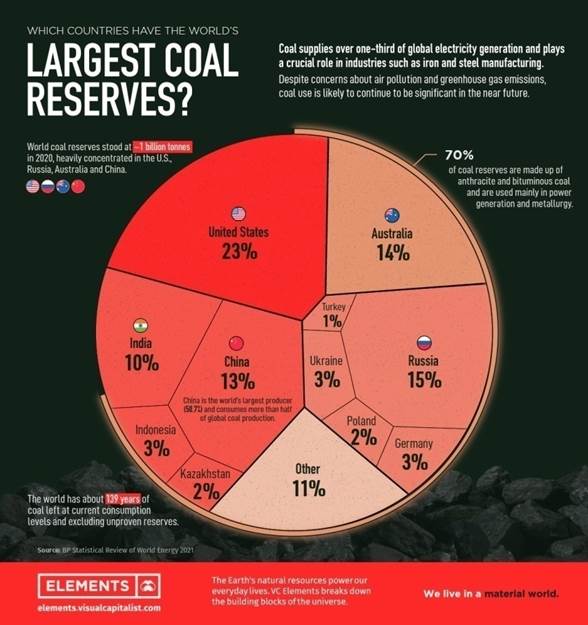

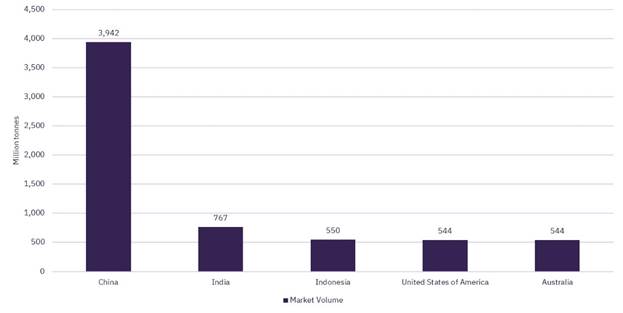

Coal Producing Countries (Million Tonnes, 2021)

Coal in India

- Coal in India was first mined in 1774by East India Company in Raniganj Coalfield along the Western bank of Damodar River.

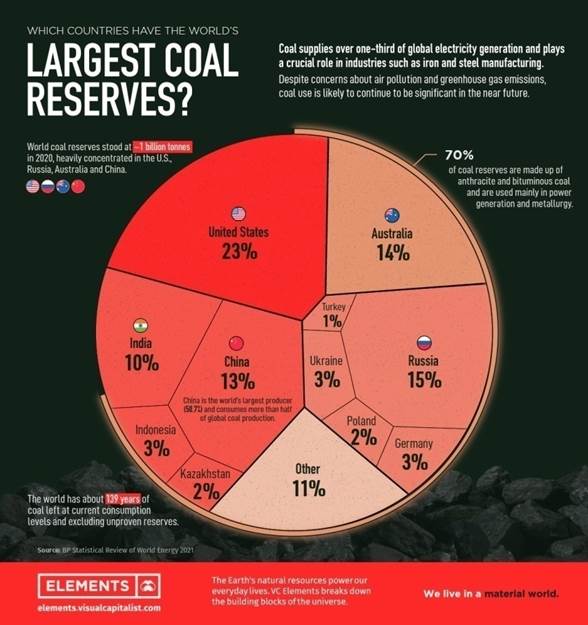

- Today, India has the fifth largest coal reserves in the world.

- India is the second largest producer of coal in the world, after China.

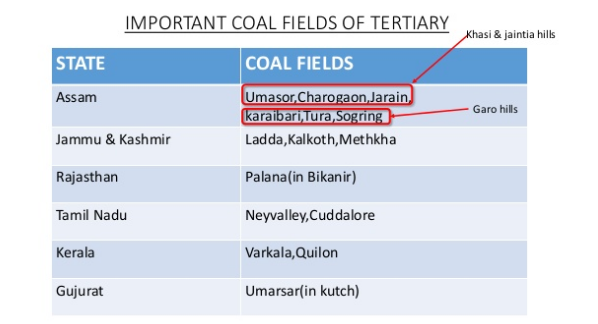

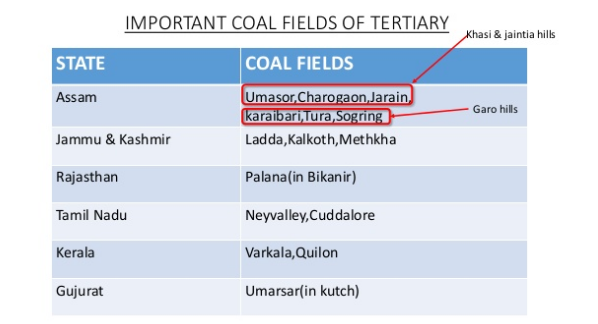

Types of coal on the basis of Time period

- Gondwana coal: Around 98 per cent of India's total coal reserves are from Gondwana times. This coal was formed about 250 million years ago.

- Tertiary coal/Lignite is of younger age. It was formed from 15 to 60 million years ago.

Distribution & Key Statistics

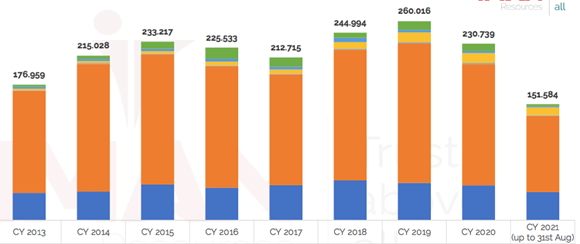

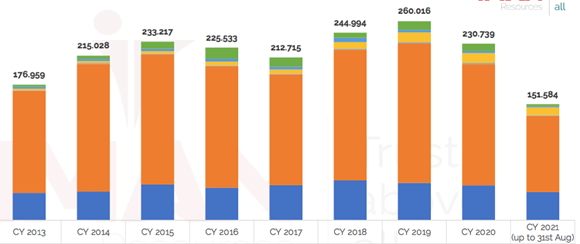

India’s grade wise coal imports

Green: Pet Coke

Blue: Met Coke

Yellow: PCI Coal

Ash: Anthracite

Orange: Thermal Coal

Deep Blue: Coking Coal

* Coking coal, is a grade of coal that can be used to produce good-quality coke. Coke is one of the key irreplaceable inputs for the production of steel. There are many varieties of coal in the world, ranging from brown coal or lignite to anthracite. Coke is produced by heating coking coals in a coke oven in a reducing atmosphere.

*Petroleum coke is a byproduct of the oil refining process.

Why does India import coal when it has enough?

- India does not have enough reserves of good quality coal especially coking coal that is used as a raw material in steel making and allied industries.

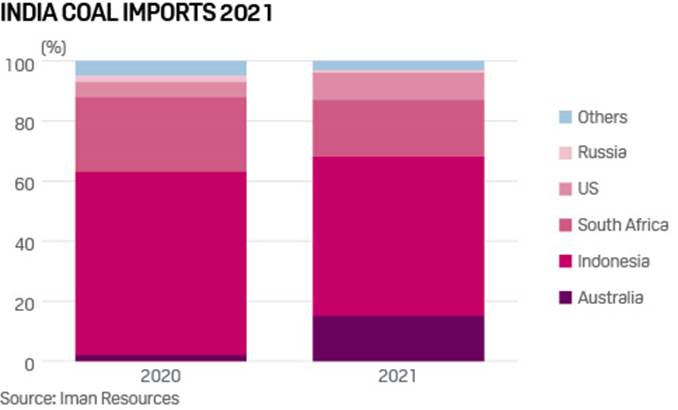

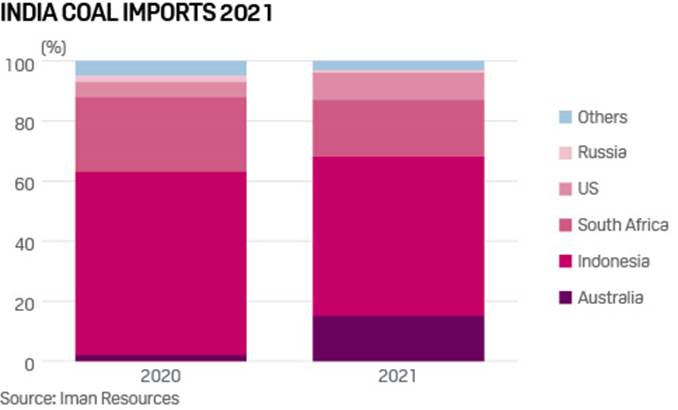

- Most of it is imported from Indonesia, South Africa, Russia and Australia.

- Thus, the imports are mainly to compensate the lack of good quality coal, especially coking coal.

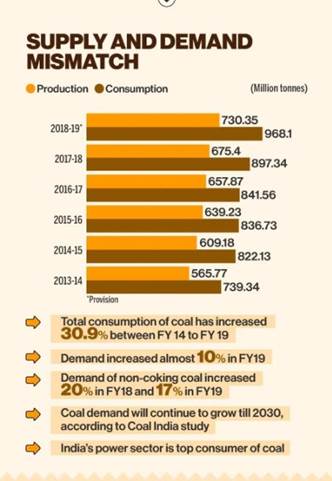

- Plus, there is a gap between demand and domestic production capacity.

- In FY19, the country produced around 730 mt of coal, while the consumption was close to 965-970 mt.

Solutions

- For Coking coal India would have to depend upon imports only.

- However, rest of the imports can be substituted by ramping up coal production.

- For these, bottlenecks in domestic coal production need to be removed. Eg- issues in acquiring land and strict rules and regulations; mismatch of demand and supply of railway wagons for transportation & coal off take; issues in clearances etc.

- The government has been progressively liberalizing the coal sector in recent times.

Examples:

- National Mineral Policy (NMP) approved in 2019, to ensure transparency in the allotment of mining blocks.

- 100% FDI under the automatic approval route allowed for the sale of coal and coal mining activities.

- Amendment of Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act (MMDRA) 1957, for seamless transfer of clearances.

- Removal of end user restrictions. Permitting commercial coal mining for local and global firms. Now, private players can participate in the auctions.

Note: The Coal Industry in India was nationalized during 1972-73.

Problems and their causes in India’s Coal Industry

Shortage in Coal Extraction

- Of the total coal reserves in India, proven reserves — that is reserves available for extraction which are economically viable, feasible and at geological exploration level — account for almost 47 per cent.

- About 44 per cent coal reserves are indicated while 9 per cent are inferred according to the Energy Statistics India 2021 Report.

- The total estimated reserves of coal in 2020 were 344.02 billion tonnes. This is an addition of 17.53 billion tonnes over 2019 in the corresponding period. This translates to 161.68 billion tonnes of proven reserves available for extraction.

- So, less than 0.45 per cent of available reserves are being extracted annually, showing that paucity of reserves is not behind the lower supply of coal.

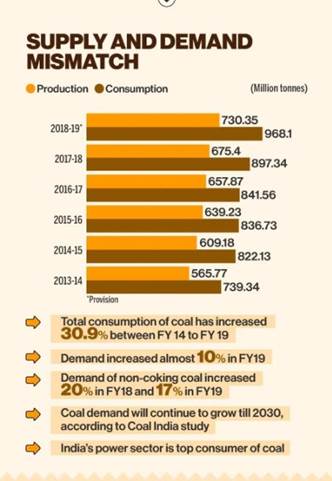

Demand Supply mismatch

- Supply of coal has not kept pace with the increase in demand.

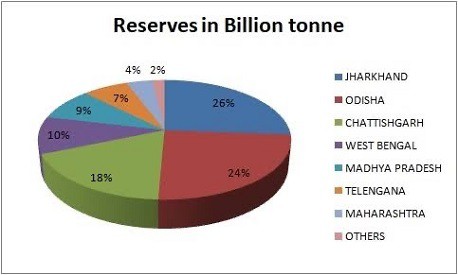

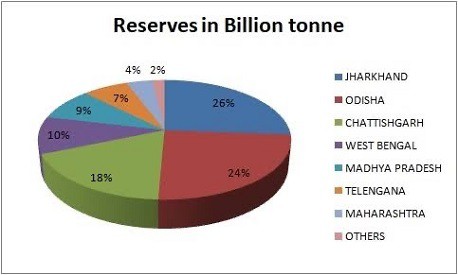

- The top three States with the highest coal reserves — Jharkhand, Odisha, and Chhattisgarh — account for approximately 70 per cent of the total coal reserves in the country. Despite the availability of coal, actual production has gone down in the last three years. There has been an upward trend in the consumption of coal in the country.

- The coal demand fulfilled has been declining over the years. In 2020-21, only 86.1% of the coal demand was met. This was primarily due to a fall in coal production within the country in 2020-21.

No mandatory Coal Washing

- A process like coal washing was supposed to be good for everyone; thermal power plants would have fewer operational problems due to poor coal quality, combustion of washed coal would be better from an emissions and local air pollution perspective, and the unnecessary transport of large amounts of ash and non-combustible material would be minimised.

- In practice, most consumers of washed coal (both in steel and power) have regretted their decision; they were usually delivered a substandard product for which they had paid a premium.

- Much of domestic coking coal today tends to be used for power generation as steel companies prefer to import their coking coal than rely on domestic products.

Failure of India’s coal mine auction mechanism

- In the last five years, aggregate production from auctioned mines has remained less than the heights of captive coal miningprior to the Supreme Court’s de-allocation decision in 2014.

- Bringing auctioned mines into production is a long time process, and it is not likely that the current commercial coal mining regime will ever rival Coal India’s established production base.

- Majority of domestic power consumers will continue to remain dependent on Coal India.

- Very few companies (public sector or private) have been able to match Coal India’s abilityto navigate the complicated bureaucratic and political hurdles associated with opening new coal mines.

- Despite all the revisions announced in the stimulus package, new coal mine auctions are not likely to attract significant domestic or international interest except from the few large players who already exist in the sector domestically.

- International companies, which have avoided India’s coal industry so far because of regulatory and reputational issues, have zero incentive to take new risks in the coronavirus disease (Covid-19) world. Smaller Indian companies simply do not have access to credit or cash on hand to open new mines.

Weakening of Coal India’s financial position

- In addition to the usual royalty payments, cesses, taxes, and other fiscal contributions, there has been extraction of extra money from Coal India.

- Coal India has transferred tens of thousands of crore to the central government in various ways.

- Coal India’s cash could have been used to further diversify the company, reinvest in new operations, promote research and development for alternative uses of coal (like the coal gasification).

- Coal India could have been strategically repurposed as a vehicle of industrial investment to help coal-bearing regions (where it has operated for 50 years) diversify their economies.

- Coal India’s market capitalization is less than a third of what it was in 2014.

Spectacular rise of the mine development operator (MDO) mode of mining

- Subcontracting of mine operations has been a major feature of the coal industry for more than two decades now.

- It has also brought considerable financial and operational efficiencies to Coal India.

- MDO model remains rife with problems related to transparency, undue transfer of gains to private entities and a general deterioration of social contract in mining regions.

- In fact, the retreat of Coal India from the front lines and the increasing use of various forms of subcontracting has led to a much harsher face of mining in India today.

- The MDO model also creates an incentive mismatch; why would a large mining company take the risks of buying a mine if they could make good money subcontracting for coal block owning public sector units instead.

No Go Zones

- In 2009, the environment ministry had placed the country's forested areas under two categories - Go and No-Go - and imposed a ban on mining in the 'No-Go' zones on environmental grounds.

- Based on this categorisation, the ministry has barred mining in hundreds of coal blocks that hold millions of tonnes reserves as they fall in the 'No-Go' or dense forest zone.

- The environment ministry's ban on mining in areas of thick forest cover has locked away millions of tonnes of coal reserves.

Drying up financing for new thermal power plants, private sector announcements of exiting the business, and declining plant load factors have been stoking pessimism about the future of the industry.

Recommendations

Increase production and competition: Leverage higher producing mines to enable more world-scale operations

- There is need to liberalize the coal mining regime by providing more autonomy to bigger mines.

- One of the suggestions for increasing production without breaking Coal India into constituent subsidiaries is to develop the large scale operations into independent entities or companies devoid of legacy end-use linkages but with an ability to sell coal in the open market(which is now possible with commercial mining).

Revisit coal grades pricing mechanism from grades based on coal mined to grades based on coal desired for end use

- This addresses intra-grade variation in energy content of coal. Without uniform pricing of energy content, and slippage on delivered grades, consumers struggle to get their feed quality right.

Increase market participation and ability to raise finances: With a competitive coal mining sector in the country, the ability to raise competitive finance should also improve

- International investment in domestic coal mining is contingent with a liberalized regime for exploration and development of coal blocks. Although 100 per cent foreign direct investment is allowed in this sector, investment is limited due to restrictions on exploration and development of a coal block.

- This policy structure needs to be reconsidered in light of sector specific requirement of a risk capital for investment.

- Moving forward, there needs to be a HELP-like policy (hydrocarbon exploration and licensing policy) for a unified licence for all coal operation types (coalbed methane, coal to Liquid, coal gasification and mining) with suitable risk sharing/pooling mechanisms.

- Additionally, an easy entry and exit for companies in this space at all levels including exploration and junior minerswould promote future investment.

Coal mining needs to be facilitated with offtake routes for bulk transportation over long distances: with railways projects delayed for long periods of time it is imperative to look at alternatives

- Logistics availability and co-ordination in offtake arrangements for coal through railways needs dedicated private lines to be built in areas where future mining capacity will come up.

- The Indian Railways continues to be resource constrained hence private investment through either a build-own-operate or a build-own-operate-transfer model in addition to customer-owned merry-go-round systems may be looked at for speedy execution of projects to ensure logistical connectivity.

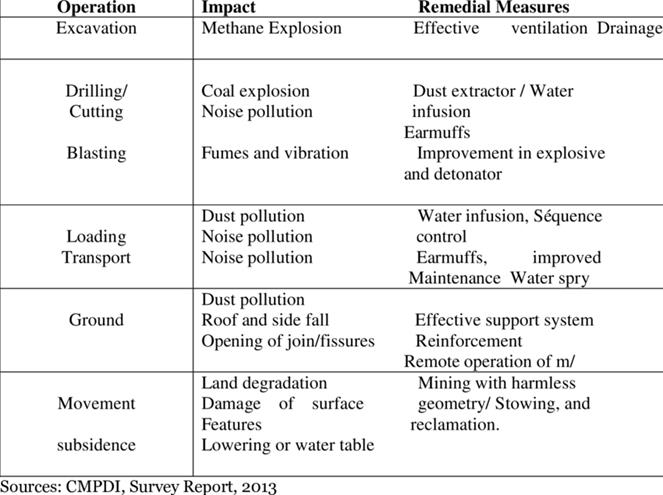

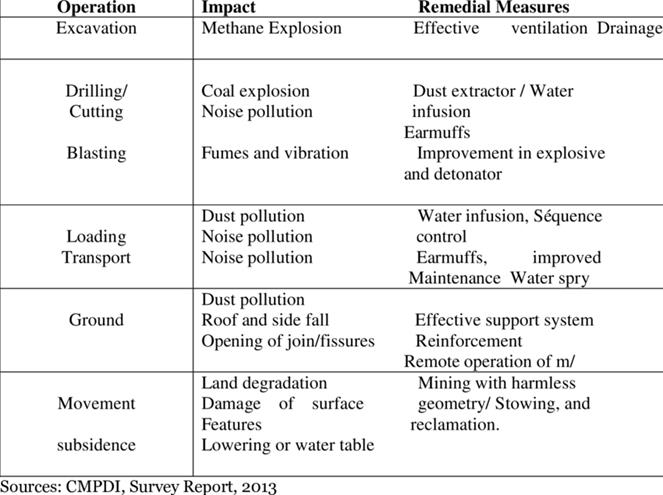

Environmental Problems of Coal Industry

There are numerous damaging environmental impacts of coal that occur through its mining, preparation, combustion, waste storage, and transport.

Acid Mine Drainage

- Acid mine drainage (AMD) refers to the outflow of acidic water from coal mines or metal mines that can wash into nearby rivers and streams.

Air Pollution

- Air pollution from coal-fired power plants includes sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter (PM), and heavy metals, leading to smog, acid rain, toxins in the environment.

- Coal- and lignite-based thermal power plants on an annual basis emit 1.3 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent / year, which is a third of the total greenhouse gas emissions in the country.

- In India, coal-fired power plants contribute 40 per cent of India’s fossil fuel emissions and 13 per cent of the ambient PM 2.5. Each year, they cause an estimated 112,000 deaths and generate around 200 MT of ash, which could lead to severe health disorders if not properly disposed of or managed.

Impact on Climate

- Climate impacts of coal plants - Coal-fired power plants are responsible for carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, making coal a huge contributor to global warming. Black carbon resulting from incomplete combustion is an additional contributor to climate change.

Coal Fires

- Coal fires occur in both abandoned coal mines and coal waste piles. Internationally, thousands of underground coal fires are burning now. Global coal fire emissions are estimated to include 40 tons of mercury going into the atmosphere annually, and three percent of the world's annual carbon dioxide emissions.

Coal Combustion Waste

- It is disposed of in landfills or "surface impoundments," which are lined with compacted clay soil, a plastic sheet, or both. As rain filters through the toxic ash pits year after year, the toxic metals are leached out into the local environment.

Coal Sludge

- Coal sludge, also known as slurry, is the liquid coal waste generated by washing coal. It is typically disposed of at impoundments located near coal mines, but in some cases it is directly injected into abandoned underground mines. Since coal sludge contains toxins, leaks or spills can endanger underground and surface waters.

Groundwater degradation

- Loss or degradation of groundwater - Since coal seams are often serve as underground aquifers, removal of coal beds may result in drastic changes in hydrology after mining has been completed.

Heavy Metals, Particulates and Radioactivity

- Heavy metals and coal - Many of the heavy metals released in the mining and burning of coal are environmentally and biologically toxic elements, such as lead, mercury, nickel, tin, cadmium, antimony, and arsenic, as well as radio isotopes of thorium and strontium.

- Particulates and coal - Particulate matter (PM) includes the tiny particles of fly ash and dust that are expelled from coal-burning power plants. Studies have shown that exposure to particulate matter is related to an increase of respiratory and cardiac mortality.

- Radioactivity and coal - Coal contains minor amounts of the radioactive elements, uranium and thorium. When coal is burned, the fly ash contains uranium and thorium "at up to 10 times their original levels.

Subsidence

- Subsidence - Land subsidence may occur after any type of underground mining, but it is particularly common in the case of longwall mining.

Thermal Pollution

- Thermal pollution from coal plants is the degradation of water quality by power plants and industrial manufacturers - when water used as a coolant is returned to the natural environment at a higher temperature, the change in temperature impacts organisms by decreasing oxygen supply, and affecting ecosystem composition.

Coal Waste

- Waste coal, also known as "culm," "gob," or "boney," is made up of unused coal mixed with soil and rock from previous mining operations. Runoff from waste coal sites can pollute local water supplies.

Water consumption and pollution

- Water consumption from coal plants - Power generation has been estimated to be second only to agriculture in being the largest domestic user of water.

- Water pollution from coal includes the negative health and environmental effects from the mining, processing, burning, and waste storage of coal.

UN described the phasing out of coal from the electricity sector as “the single most important step to get in line with the 1.5 degree-goal of the Paris Agreement.”

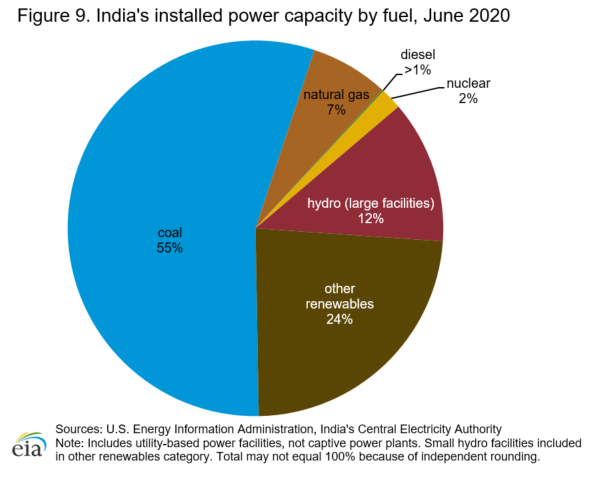

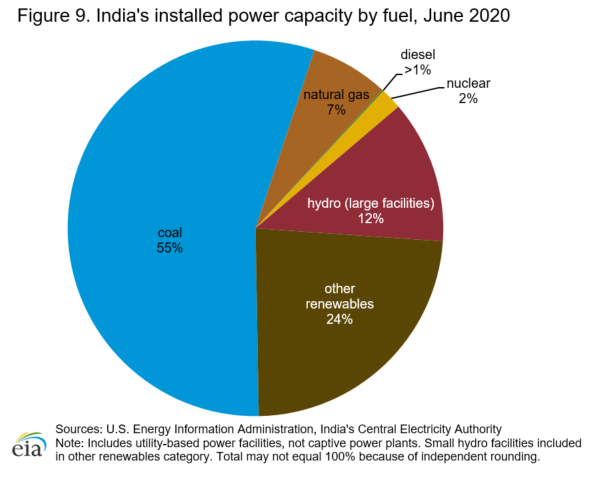

Coal’s importance in the Indian economy

- Historically, coal plants have accounted for 70 to 80 per cent of the country’s total power generation. This share is estimated to remain above 50 per cent even in 2030.

- Further, India’s current installed coal capacity of 209 GW is set to expand. Coal is a reliable energy source, especially when compared with the seasonal and diurnal variability of renewables.

- Abundant in India, it is considered important for the nation's energy security and is a key source of revenue for the government.

- The state-owned Coal India Limited (CIL) is the largest coal miner in the world; it pays around INR 40,000 crore annually in royalties, cesses, and levies, besides rich dividend payouts to the government.

- Coal production also benefits the Indian Railways (IR), which cross-subsidises passenger fares with high freight rates for coal transportation.

Challenges to coal phase-out: Impact on livelihoods

- Coal production supports millions of lives and livelihoods – either directly or indirectly, and to varying degrees.

- A coal exit would jeopardise these livelihoods. It would also leave indirect dependents employed by auxiliary services – who are far greater in number - in the lurch. Examples include coal washery workers, traders, and transporters.

- Also at risk are those with an induced dependence on coal, such as tea sellers, grocers, and other business owners in economic hubs close to mining areas.

- Finally, there is the informal coal economy, consisting of small-scale coal operations and illegal trades.

- Scholars estimate that around 10-15 million dependents live in India’s coal belt.

Addressing challenges

- Given the environmental and social impacts of coal use, a phase-out is inevitable. Still, the shift from coal to a cleaner energy basket should not exacerbate existing inequities or create new ones.

- It should address the future of communities that have depended on the coal economy for decades. This holistic approach to the phase-out is what we mean by a “just” transition.

- In India, such a transition will only unfold gradually.

- While a complete coal phase-out may take a few decades, we need to lay out a meticulous, long-term plan for coal-dependent regions right now.

- The phase-out’s pace and intensity will largely depend on top-down governance.

- Government policy is currently geared towards ramping up coal production to meet growing domestic demand and substitute imports. Shutting down coal operations will require a conscious shift in the coal policy agenda and deliberate planning and action.

- Developing the agroforestry, fishery and ecotourism sectors could provide alternative sources of employment and economic opportunities to coal-dependent communities.

- The government could use the cash crunch induced by the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to direct funds earmarked for economic revival towards the transition.

- Finally, decentralizing India’s phase-out to the district level will aid the development of unique local solutions.

- The transition should be based on a socially inclusive and participatory planning process that uses inputs from workers, unions, local communities, district-level administrators, environmental activists, industrialists.

- To achieve just transition, a planning architecture must be developed at the district-level defining timeframe, establishing an inclusive transition planning mechanism, providing alternative employment opportunities for formal and informal workers in the short-term, planning economic diversification, including industrial restructuring, improving social and physical infrastructure and identifying financial resources to support the whole process of a just transition.

- For “just transition” to work, support is needed from various quarters including a strong national and state government policy and financial support, a diverse coalition among stakeholders, local engagement, economic diversification and social security planning, social and physical infrastructure development, and serious public and private sector investment.

https://epaper.thehindu.com/Home/ShareArticle?OrgId=GHKA93RHT.1&imageview=0