Free Courses Sale ends Soon, Get It Now

Free Courses Sale ends Soon, Get It Now

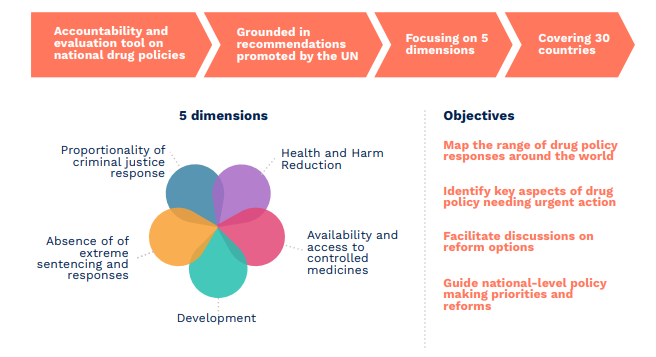

The inaugural Global Drug Policy Index, has been released by the Harm Reduction Consortium

Finding of the report:

© 2024 iasgyan. All right reserved