Free Courses Sale ends Soon, Get It Now

Free Courses Sale ends Soon, Get It Now

Disclaimer: Copyright infringement not intended.

Context

What is RWH?

Why harvest rain?

India’s water crisis

2018 Composite Water Management Index

Its conclusion: ‘India is suffering from its worst water crisis in its history.’

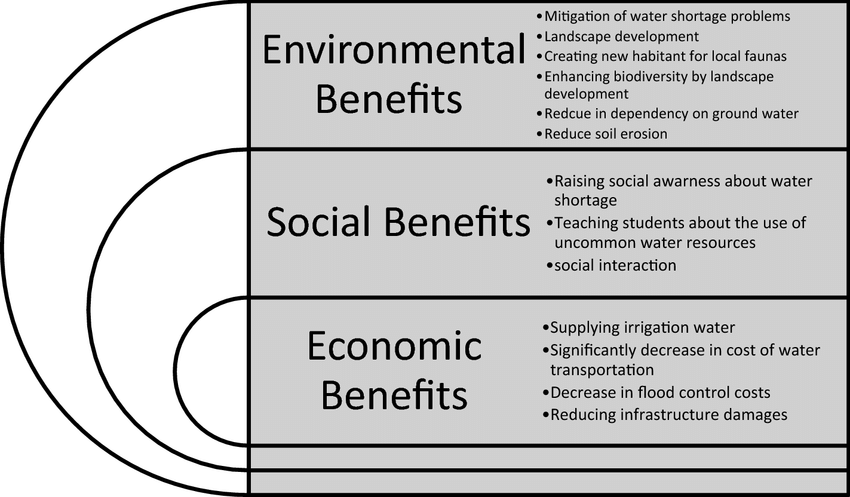

Benefits of Rainwater Harvesting

Disadvantages of rainwater harvesting

Rainwater harvesting in India: Traditional and contemporary

Water Harvesting in Indian History

|

321– 291 BC |

Kauṭilya’s Arthaśāstra gives an extensive account of dams and bunds that were built for irrigation during the Mauryan Empire by Chandragupta Maurya. These were managed and regulated with a clear set of rules. Severe punishments were imposed for causing damage to property by flooding, owners of higher tanks preventing the filling of the lower tank and failing to maintain the water bodies. So much so that death penalty was prescribed for breaking a reservoir or tank full of water! Different types of taxes were collected on water drawn from natural sources like rivers, tanks and springs versus water drawn from storage structures built by the king. The tax rate varied according to the method of drawing water. In the absence of the owner, the waterbodies were maintained by the people of the village (Public Health Engineering Department, Meghalaya, n.d.). |

|

First century BC |

A very sophisticated example of hydraulic engineering is found in Sringaverapura near Allahabad. It comprises of three percolation-cum-storage tanks, fed by an 11 m wide and a 5 m deep canal that was used for floodwater harvesting from the Ganga during heavy monsoons. |

|

Second century AD |

Large-scale development of lakes and well irrigation are seen during the time of the Pandya, Chera and Chola dynasties in South India. Natural depressions in the landscape were developed into large irrigation tanks. The Grand Anicut or Kallanai built by Karikala Chola across the river Cauvery to divert water for irrigation is still functional. It is the fourth-oldest water-regulator structure in the world which is still in use today (Water-technology.net 2013). |

|

Eleventh century AD |

King Bhoja of Bhopal built the largest artificial lake (65,000 acres) in India, fed by streams and springs, originally called Bada Talab (Big Pond) and now Bhojtal (Upper Lake). |

|

Twelfth century AD |

Rajatarangini by Kalhana describes a well- maintained irrigation system in Kashmir where structures exist around the Dal and Anchar lakes and the Nandi Canal (M. Matthews 2001). |

Examples of Traditional Water Management Techniques Still in Use Today:

Northern India

Kuls/Kuhls (Himachal Pradesh)

Long channels mainly found in Himachal Pradesh and in some parts of Jammu and Kashmir. The kul begins at the glacier and leads into a circular tank from where, when water is needed to irrigate the fields, a trickle of water is let out. This distribution is regulated by the villagers.

Araghatta (Kashmir)

Araghattas are water wheels found in the Kashmir Valley. Also known as the Persian wheel, these wooden wheels help lift water from the river Jhelum to the complex irrigation system of canals which irrigate rice fields in the Valley.

Johads (Rajasthan and Haryana)

Johads are small earthen check dams that hold rainwater, aiding groundwater recharge and slow percolation to the underground aquifer.

Khadins

Khadins are ingenious constructions designed to harvest surface runoff water for agriculture. The main feature of a khadin, also called dhora, is a long earthen embankment that is built across the hill slopes of gravelly uplands. Sluices and spillways allow the excess water to drain off and the water-saturated land is then used for crop production. First designed by the Paliwal Brahmins of Jaisalmer in the 15th century, this system is very similar to the irrigation methods of the people of ancient Ur (present Iraq).

Jhalaras

Jhalaras are typically rectangular-shaped stepwells that have tiered steps on three or four sides. These stepwells collect the subterranean seepage of an upstream reservoir or a lake. Jhalaras were built to ensure easy and regular supply of water for religious rites, royal ceremonies and community use. The city of Jodhpur has eight jhalaras, the oldest being the Mahamandir Jhalara that dates back to 1660 AD.

Talabs

Talabs are reservoirs that store water for household consumption and drinking purposes. They may be natural, such as the pokhariyan ponds at Tikamgarh in the Bundelkhand region or man made, such as the lakes of Udaipur. A reservoir with an area less than five bighas is called a talai, a medium sized lake is called a bandhi and bigger lakes are called sagar or samand.

Bawaris

Bawaris are unique stepwells that were once a part of the ancient networks of water storage in the cities of Rajasthan. The little rain that the region received would be diverted to man-made tanks through canals built on the hilly outskirts of cities. The water would then percolate into the ground, raising the water table and recharging a deep and intricate network of aquifers. To minimise water loss through evaporation, a series of layered steps were built around the reservoirs to narrow and deepen the wells.

Taanka

Taanka is a traditional rainwater harvesting technique indigenous to the Thar desert region of Rajasthan. A Taanka is a cylindrical paved underground pit into which rainwater from rooftops, courtyards or artificially prepared catchments flows. Once completely filled, the water stored in a taanka can last throughout the dry season and is sufficient for a family of 5-6 members. An important element of water security in these arid regions, taankas can save families from the everyday drudgery of fetching water from distant sources.

Nadi

Found near Jodhpur in Rajasthan, nadis are village ponds that store rainwater collected from adjoining natural catchment areas. The location of a nadi has a strong bearing on its storage capacity and hence the site of a nadi is chosen after careful deliberation of its catchment and runoff characteristics. Since nadis received their water supply from erratic, torrential rainfall, large amounts of sandy sediments were regularly deposited in them, resulting in quick siltation. A local voluntary organisation, the Mewar Krishak Vikas Samiti (MKVS) has been adding systems like spillways and silt traps to old nadis and promoting afforestation of their drainage basin to prevent siltation.

Kuhls

Kuhls are surface water channels found in the mountainous regions of Himachal Pradesh. The channels carry glacial waters from rivers and streams into the fields. The Kangra Valley system has an estimated 715 major kuhls and 2,500 minor kuhls that irrigate more than 30,000 hectares in the valley. An important cultural tradition, the kuhls were built either through public donations or by royal rulers. A kohli would be designated as the master of the kuhl and he would be responsible for the maintenance of the kuhl.

Southern India

Kovil Kulam (Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala)

The tanks vary in size and shape with corridors and long flights of steps surrounding them. Intricate inlet channels bring water from a stream or river and outlets carry away the excess water.[19]

Surangas (Western Ghats)

These horizontal structures are tunnel-like wells that use gravitational force for extraction of groundwater and then collect it into a storage tank. This is then used for irrigation.

Eri (Tamil Nadu)

The Eri (tank) system of Tamil Nadu is one of the oldest water management systems in India. Still widely used in the state, eris act as flood-control systems, prevent soil erosion and wastage of runoff during periods of heavy rainfall, and also recharge the groundwater. Eris can either be a system eri, which is fed by channels that divert river water, or a non-system eri, that is fed solely by rain. The tanks are interconnected in order to enable access to the farthest village and to balance the water level in case of excess supply. The eri system enables the complete use of river water for irrigation and without them, paddy cultivation would have been impossible in Tamil Nadu.

Panam Keni (Kerala)

The Kuruma tribe (a native tribe of Wayanad) uses a special type of well, called the panam keni, to store water. Wooden cylinders are made by soaking the stems of toddy palms in water for a long time so that the core rots away until only the hard outer layer remains. These cylinders, four feet in diameter as well as depth, are then immersed in groundwater springs located in fields and forests. This is the secret behind how these wells have abundant water even in the hottest summer months.

Eastern India

Ahar Pynes (South Bihar)

Ahar Pynes are traditional floodwater harvesting systems indigenous to South Bihar. Ahars are reservoirs with embankments on three sides that are built at the end of diversion channels like pynes. Pynes are artificial rivulets led off from rivers to collect water in the ahars for irrigation in the dry months. Paddy cultivation in this relatively low rainfall area depends mostly on ahar pynes.

Johads

Johads, one of the oldest systems used to conserve and recharge ground water, are small earthen check dams that capture and store rainwater. Constructed in an area with naturally high elevation on three sides, a storage pit is made by excavating the area, and excavated soil is used to create a wall on the fourth side. Sometimes, several johads are interconnected through deep channels, with a single outlet opening into a river or stream nearby. This prevents structural damage to the water pits that are also called madakas in Karnataka and pemghara in Odisha.

Jackwells

The Shompen tribe of the Great Nicobar Islands lives in a region of rugged topography that they make full use of to harvest water. In this system, the low-lying region of the island is covered with jackwells (pits encircled by bunds made from logs of hard wood). A full-length bamboo is cut longitudinally and placed on a gentle slope with the lower end leading the water into the jackwell. Often, these split bamboos are placed under trees to collect the runoff water from leaves. Big jackwells are interconnected with more bamboos so that the overflow from one jackwell leads to the other, ultimately leading to the biggest jackwell.

Western India

Virdas (Banni grassland, a part of Great Rann of Kutch, Gujarat)

Built by the nomadic Maldhari people. These unique structures are shallow wells,dug in depressions to collect rainwater, which separate freshwater from saltwater as groundwater is mostly saline.

Kunds/Kundis (Bikaner, Jaisalmer region, West Rajasthan and parts of Gujarat)

A kund is a saucer-shaped catchment area that gently slope towards the central circular underground well. Its main purpose is to harvest rainwater for drinking. Kunds dot the sandier tracts of western Rajasthan and Gujarat. Traditionally, these well-pits were covered in disinfectant lime and ash, though many modern kunds have been constructed simply with cement. Raja Sur Singh is said to have built the earliest known kunds in the village of Vadi Ka Melan in the year 1607 AD.

Bhandara Phad

Phad, a community-managed irrigation system, probably came into existence a few centuries ago. The system starts with a bhandhara (check dam) built across a river, from which kalvas (canals) branch out to carry water into the fields in the phad (agricultural block). Sandams (escapes outlets) ensure that the excess water is removed from the canals by charis (distributaries) and sarangs (field channels). The Phad system is operated on three rivers in the Tapi basin – Panjhra, Mosam and Aram – in the Dhule and Nasik districts of Maharashtra.

Ramtek model

The Ramtek model has been named after the water harvesting structures in the town of Ramtek in Maharashtra. An intricate network of groundwater and surface water bodies, this system was constructed and maintained mostly by the malguzars (landowners) of the region. In this system, tanks connected by underground and surface canals form a chain that extends from the foothills to the plains. Once tanks located in the hills are filled to capacity, the water flows down to fill successive tanks, generally ending in a small waterhole. This system conserves about 60 to 70 % of the total runoff in the region!

North-East India

The north-eastern region is one of the most ethnically diverse regions in India. Diverse indigenous water harvesting systems are prevalent here. Systems are designed with local materials making it sustainable and easy to maintain.

Bamboo drip system (Meghalaya)

Bamboo Drip irrigation System is an ingenious system of efficient water management that has been practised for over two centuries in northeast India. The tribal farmers of the region have developed a system for irrigation in which water from perennial springs is diverted to the terrace fields using varying sizes and shapes of bamboo pipes. Best suited for crops requiring less water, the system ensures that small drops of water are delivered directly to the roots of the plants. This ancient system is used by the farmers of Khasi and Jaintia hills to drip-irrigate their black pepper cultivation.

Zabo (Nagaland)

The Zabo (meaning ‘impounding run-off’) system combines water conservation with forestry, agriculture and animal care. Practised in Nagaland, Zabo is also known as the Ruza system. Rainwater that falls on forested hilltops is collected by channels that deposit the run-off water in pond-like structures created on the terraced hillsides. The channels also pass through cattle yards, collecting the dung and urine of animals, before ultimately meandering into paddy fields at the foot of the hill. Ponds created in the paddy field are then used to rear fish and foster the growth of medicinal plants.

Central India

The Pat system, in which the peculiarities of the terrain are used to divert water from hill streams into irrigation channels, was developed in the Bhitada village in Jhabua district of Madhya Pradesh. Diversion bunds are made across a stream near the village by piling up stones and then lining them with teak leaves and mud to make them leak-proof. The Pat channel then passes through deep ditches and stone aqueducts that are skilfully cut info stone cliffs to create an irrigation system that the villagers use in turn.

There are several other hyperlocal versions of the traditional method of tank irrigation in India. From keres in Central Karnataka and cheruvus in Andhra Pradesh to dongs in Assam, tanks are among the most common traditional irrigation systems in our country.

These ecologically safe traditional systems are viable and cost-effective alternatives to rejuvenate India’s depleted water resources. Productively combining these structures with modern rainwater-saving techniques, such as percolation tanks, injection wells and subsurface barriers, could be the answer to India’s perennial water woes.

Recent Community Efforts

Examples of Governmental Support and Regulations

New Technology for Water Woes:

‘Water holds the key to sustainable development. We need it for health, food security and economic progress.’

—Ban Ki-moon, Secretary-General of the United Nations (UN News Centre 2013)

The urban context

Popular methods of rainwater harvesting

Inadequate rainwater harvesting in India

Infrastructure and wastage

Other issues

Lack of implementation: Cases in point

Final Thoughts

https://epaper.thehindu.com/Home/ShareArticle?OrgId=GG9A0FK75.1&imageview=0

© 2024 iasgyan. All right reserved